P.A.L.T - the framework Anthropic accidentally proved with Claude Cowork

Most AI teams are stuck in what I’ll call the replication phase.

They’re using a revolutionary technology to do extremely non-revolutionary things:

- Write emails faster

- Generate slides quicker

- Summarize meetings more efficiently

It’s useful. But it’s not transformation. It’s the “electric candle” problem: new tech, old mindset.

Anthropic escaped that trap — not by running better surveys, but by watching people do something much more revealing: they watched users bend a developer tool into a productivity assistant.

That observation became Claude Cowork, one of the clearest examples yet of how AI products actually evolve. And it maps perfectly to a Design Sprint Academy framework worth knowing (and worth buying): P.A.L.T.

Here are the lessons.

1. The problem doesn’t show up in surveys. It shows up in workarounds.

So how did Anthropic came up with Claude Cowork?

Not through interviews. Not through feature requests. But through something far more revealing: users behaving unexpectedly.

Anthropic engineer Boris Cherny noticed users doing unexpected things with Claude Code — a terminal-based tool built for developers. Except people weren’t using it the way it was intended.

They were using it for completely different purposes, such as:

- Track plant growth

- Research vacations

- Control smart ovens

- Organize personal files

In other words: they were delegating life admin through a scary command line interface.

That might look like misuse, but in fact it was just market demand in disguise.

When users fight friction just to access a capability, they’re telling you something important: the product is pointing to a bigger job than you designed for.

But what if you don’t have usage data?

Most teams aren’t Anthropic. You may not have thousands of users bending your product in the wild. So you need another way to surface the same insight — using what you do have: cross-functional teams, empathy, observation and intuition.

That’s where collaborative AI Problem Framing workshops become powerful. Workshops help teams simulate what Anthropic saw in real usage: the workarounds, the friction, the hidden unmet needs.

Workshop methods that reveal workarounds

Proto-Personas

Capture what people actually do today — their routines, hacks, and coping mechanisms — alongside the friction they’ve normalized.

Customer Journey Maps

Lay out the user’s steps end-to-end. The goal is mapping the behavior, spotting the moments where people pause, repeat, patch, or manually compensate.

Service Blueprints

Go one layer deeper: connect user actions to the invisible backstage labor happening inside the organization. Latent AI opportunities often hide there.

Your goal with these methods is simple: find the moments where people tolerate absurd effort.

If someone is willing to:

- Manually turn screenshots into spreadsheets

- Dig through chaotic folders every week

- Take photos of themselves and simulate outfits just to buy clothes online

That’s not just inconvenience. That friction tells you that a Painful + Latent problem is waiting for the right AI intervention.

2. AI Products start with solutions, not problems

This is the counterintuitive part.

Human-centered design literature, and even our own mantra at Design Sprint Academy is about following the classic script: Identify problem → validate solution → build solution

Anthropic added two more steps to the flow: Ship powerful capability → observe behavior → identify problem → validate solution → build solution

The mindset behind it was simple: "prototype-first, scale-what-works".

Claude Code was meant to be a tool for developers — positioned as a coding companion, almost like a junior engineer acting directly in your environment. But once users had the capability in their hands, they used it for completely different purposes: to solve problems they couldn’t even articulate before.

That raises an important question:

Why should AI products start with solutions, not problems?

Because when the technology is new, the problem space is invisible.

Problem-first discovery assumes something big: that customers already know what they need.

But with new technology, they don’t.

Nobody asked for:

- Search engines back in early 1990s

- Smartphones back in the mid-2000s

- Autocomplete back in 2004

- Google Maps back in 2005

- AI agents back in 2023

Not because people didn’t want them… but because they didn’t have the mental model.

AI expands the territory of “what’s possible”. And until users touch that possibility, they can’t describe the opportunity.

Latent problems are pre-language. They only become speakable after the solution exists.

Starting with solutions it’s often the only honest way to surface the next generation of problems.

This is also why we begin our own AI Problem Framing process the same way: by working from capability → behavior → opportunity.

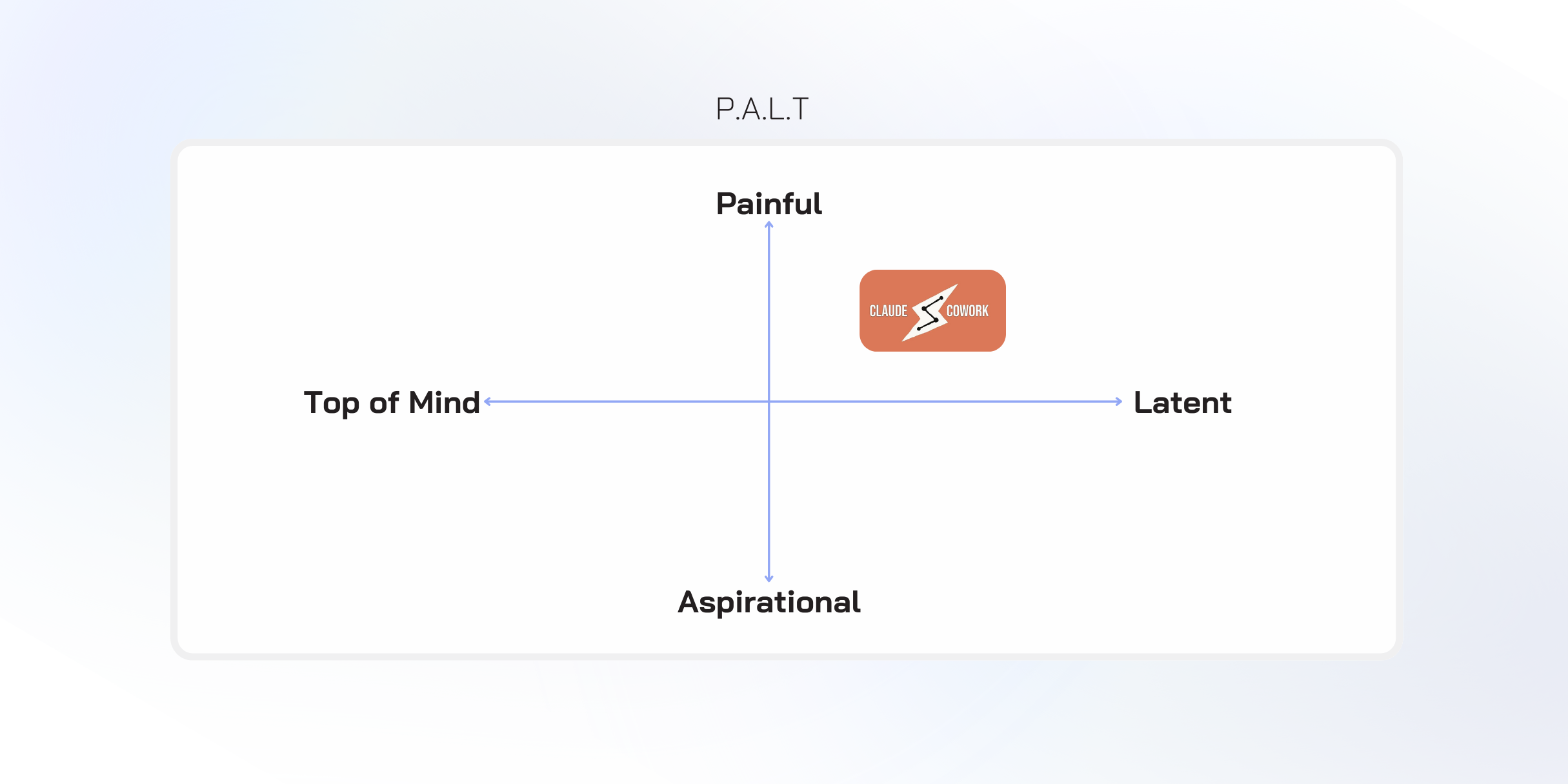

3. Claude Cowork solved a “Painful + Latent” problem

This is where P.A.L.T. becomes more than a framework, it becomes a strategic lens.

Because not all customer problems are created equal. Some are obvious. Some are loud. And some — the most valuable ones — are hiding in plain sight.

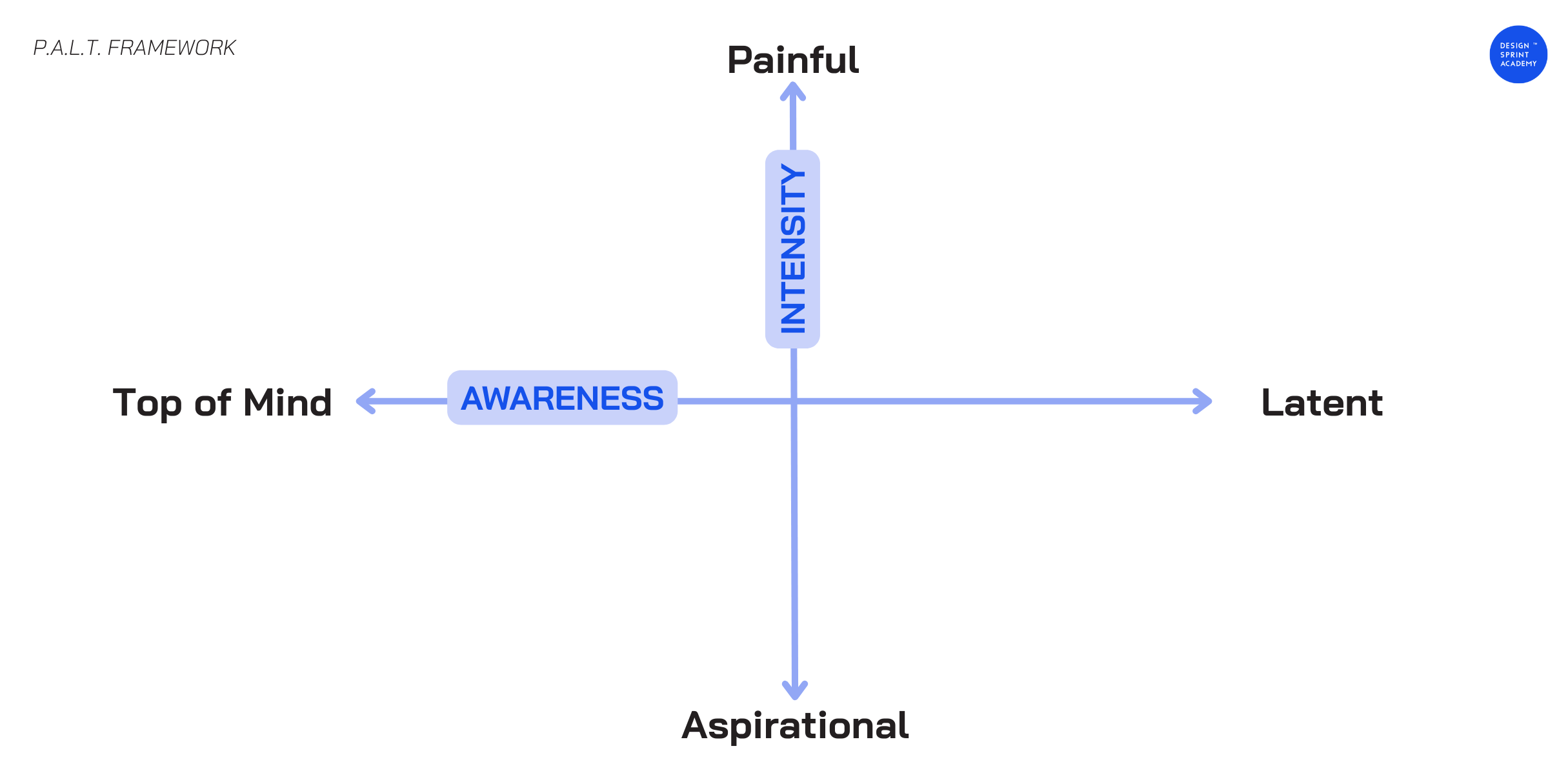

P.A.L.T. helps teams sort problems by two simple dimensions:

How intense is the need?

How aware is the user of it?

P.A.L.T. stands for:

- Painful → A problem that hurts, costs time, money, or trust.

- Aspirational → A desire or wish that would feel good to achieve, but not critical.

- Latent → A hidden issue or desire the user hasn’t yet recognized or can’t clearly express.

- Top of Mind → Something the user is already aware of and actively thinking about.

It maps needs across two forces: Awareness + Intensity

We built P.A.L.T. at Design Sprint Academy as a practical tool for AI discovery pods to sort customer needs with more precision — and to see how those needs shift depending on the context, the moment, or even the persona you’re designing for.

Why this matters

Most teams build for what users can clearly explain:

- Top-of-mind complaints.

- Feature requests.

- Loud frustrations.

But Claude Cowork didn’t come from a loud problem. It came from a quiet one … a painful form of digital drudgery that users had normalized… until Anthropic showed them another way.

People weren’t saying: “Please build an autonomous desktop agent.”

They were doing something more honest:

- Turning receipt screenshots into spreadsheets

- Wrestling chaotic folders into order

- Fighting through a developer CLI just to avoid repetitive work

That’s classic Painful + Latent territory: High friction. High cost. Low articulation.

Users feel the pain… but they don’t yet have language for the solution.

Anthropic made it visible. They took a hidden problem and moved it into the center of attention — from latent to impossible to ignore.

.png)

Innovation lives beyond top-of-mind problems

Top-of-mind problems are easy to spot. Everyone can see them — including your competition.

They show up in support tickets. They dominate user interviews. They flood feature request boards. They’re real. But they’re also obvious.

Which means they’re usually crowded, competed away, and solved in incremental ways.

Breakthrough AI products tend to come from a different place: painful + latent problems.

The ones users live with every day… but can’t clearly name yet — because they’ve normalized the friction, or because they don’t realize a better workflow is even possible.

PALT helps teams find those moments — before the market has words for them.

So the real question is:

Are you building what your roadmap says users want… Or what their behavior is already proving they need?

.png)