How to use the AI Problem Framing Canvas

A decision path for teams under real AI pressure

AI rarely fails because a team can’t build. In 2025 we saw how fast execution got.

It fails earlier: teams commit to the wrong problem, then notice too late—when time, trust, and budget are already sunk.

If you lead or support AI work, you’ve probably watched this happen.

Where AI initiatives actually start

Most AI efforts don’t begin with a clear strategy. They begin with a pile of ideas.

Those ideas come from everywhere:

- a mandate from leadership (“We need to do something with AI”)

- a team demoing new tools (“Look what we can do”)

- a backlog full of “we should use AI here”

- competitor noise and outside pressure

Early on, everything looks promising. Nothing looks obviously wrong.

And that’s precisely the problem.

Idea volume creates the illusion of progress, while quietly eroding decision quality.

The comfy middle: activity disguised as progress

What usually follows is a familiar phase.

Teams start working. Workshops are run. Concepts are explored. Prototypes appear. Stakeholders feel involved. Demos everywhere.

From the outside, it looks like momentum. Inside, feels like progress.

And then, later in the game, reality shows up. This is the moment most AI initiatives don’t recover from.

You learn that:

- ❌ your data, timeline, or stack can’t support the approach

- ❌ it doesn’t fix a problem customers care about

- ❌ nobody can tie it to a business goal

- ❌ it won’t fit into the systems you already run

By then:

- people are invested

- expectations are set

- stopping has a political and emotional price

So the team keeps going—not because it’s right, but because stopping is hard. That’s a decision-timing failure.

The big question: what if you knew earlier?

You usually discover the constraints after the build starts—after the team is attached, after the plan has a name, after it becomes “the thing we already started.”

Move that discovery up front, while changing course is still cheap.

That’s what the AI Problem Framing Canvas is for.

.png)

Why the AI Problem Framing Canvas starts with the Idea

The canvas does something that feels counterintuitive at first. It doesn’t start with users. Or data. Or the business goal.

It starts with the AI idea.

Why we designed it this way? Because it’s where the energy already is. And in all our experience at Design Sprint Academy running decision-making workshops across the globe, across cultures, across industries, we noticed better results every time we started from where people are. Our mantra: "don't fight human nature", instead work with it.

Writing the idea down does one thing well: it makes the thinking visible.

When an idea stays in someone’s head, it grabs attention, eats working memory, and turns feedback into a personal critique. It also stays tied to the person who first said it.

Putting the idea on the canvas moves it onto the page. That creates distance. It lowers the emotional grip. And it gives the person holding it room to judge it like any other option.

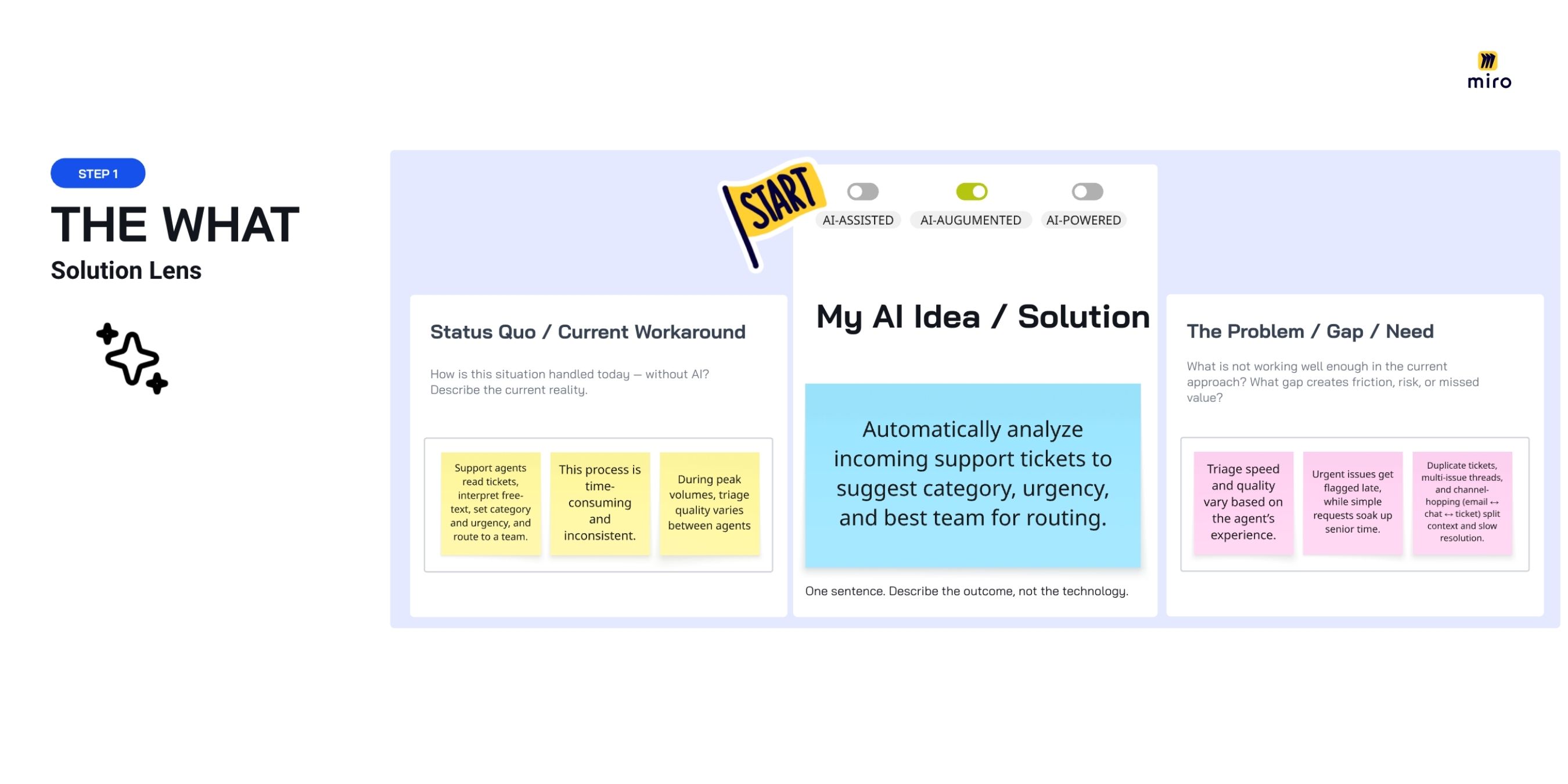

STEP 1 — THE WHAT: grounding the idea in reality

My AI idea / solution

You start by writing the idea in one sentence — describing the outcome, not the technology.

For example, someone working in Customer Support at a large organization might have this idea: “Analyze incoming support tickets to suggest category, urgency, and the best team for routing.”

Notice what’s missing: model names, architecture, tools. What’s included: the change you want in the system.

After you write the idea, answer one additional question that prevents a lot of confusion later: Where does this idea sit in the automation spectrum - AI-assisted, AI-augmented, or AI-powered?

This isn’t labeling for the sake of it. It sets expectations about the magnitude of the change.

AI-assisted

AI supports a human task or choice.

- A human stays in control

- AI offers suggestions, insights, or recommendations

- Responsibility and accountability stay with the human

In the support example, AI might suggest a category or urgency — but a person decides.

AI-augmented

AI changes how a task is done.

- Parts of the workflow run automatically

- A human still oversees, but does less manual work

- Speed, consistency, or quality improves in a noticeable way

In the support example, tickets get routed automatically, with human review for edge cases.

AI-powered

AI does the job end to end.

- Decisions or actions run automatically

- A human steps in only for exceptions

- Trust, risk, and governance move to the center

In the support example, tickets are routed and prioritized without human review.

Why the distinction matters: it sets expectations for risk, responsibility, and scope.

A lot of AI work blows up not because the idea is bad, but because different people pictured different levels of automation.

Status quo / current workaround

Next, you describe how things work today — without AI.

Following our example you might write: “Support agents read tickets, interpret free-text, set category and urgency, and route to a team using experience and local rules. During peak volume, triage varies by between agents. The work is slow and inconsistent.”

This block makes people slow down and look at the real operating context.

When teams write the status quo plainly, they notice things they were stepping over:

- manual work nobody named

- unofficial rules and shortcuts that keep the queue moving

- variation from experience, fatigue, or pressure

- risks hidden behind “it usually works”

This is also where attachment shows up. People built these workarounds to survive complexity. They feel familiar—sometimes protective. If you skip the current reality, you jump straight to “better” without knowing what you’re improving from.

And without a baseline, “better” is just a story, not something you can measure, compare, or check later.

The problem / gap / need

Only now do you spell out what isn’t working, where the drag is, and where risk or lost value shows up today.

Examples:

- “Triage speed and quality swing based on the agent’s experience.”

- “Urgent issues get flagged late, while simple requests soak up senior time.”

- “Duplicate tickets, multi-issue threads, and channel-hopping (email ↔ chat ↔ ticket) split context and slow resolution.”

- “Many tickets arrive unclear or incomplete: missing context, vague descriptions, no repro steps, and little supporting material (screenshots, logs, error messages).”

At this point you’re not selling a solution. You’re naming why the current setup falls short.

This block turns vague discomfort into a shared problem hypothesis—something stakeholders can later rank, test, or reject.

STEP 2 — THE WHY: define the aim

Here the canvas changes the lens.

A problem is only a problem if it stands in the way of a goal.

If you don’t name the goal, you’re not solving anything—you’re exploring.

And if you can’t tie the idea to a goal leadership already cares about, it won’t get staffed, funded, or shipped. The first question will be: What does this help us achieve, and is it a priority right now?

Business domain

Place the problem inside the org.

Where does it live—Sales, Marketing, Operations, Finance, Product/Platform? In our example: Customer Support.

Business goal / KPI / strategic priority

Now connect the idea to a business goal.

Most teams already have priorities, KPIs, or OKRs. Your job isn’t to invent a new one. It’s to name which existing one this idea serves.

In customer support, that might be: “Cut average response time by X% and raise first-contact resolution, without adding headcount.”

This step forces a shift in perspective.

The idea is no longer evaluated on how interesting it sounds. It’s judged on whether it helps the business win the thing it’s trying to win right now.

Once you make this mapping intentional, one of two things happens.

Either: you find a clear connection, and the idea earns the right to move forward

Or: you don’t find a connection, and you learn the idea doesn’t match today’s priorities.

That second outcome isn’t a loss. It usually means the timing is wrong.

From there you can choose what to do with it:

- drop it

- park it

- bring it back when priorities shift

This block turns strategy into a day-to-day filter, so teams don’t spend weeks building work that leadership can’t justify.

.jpg)

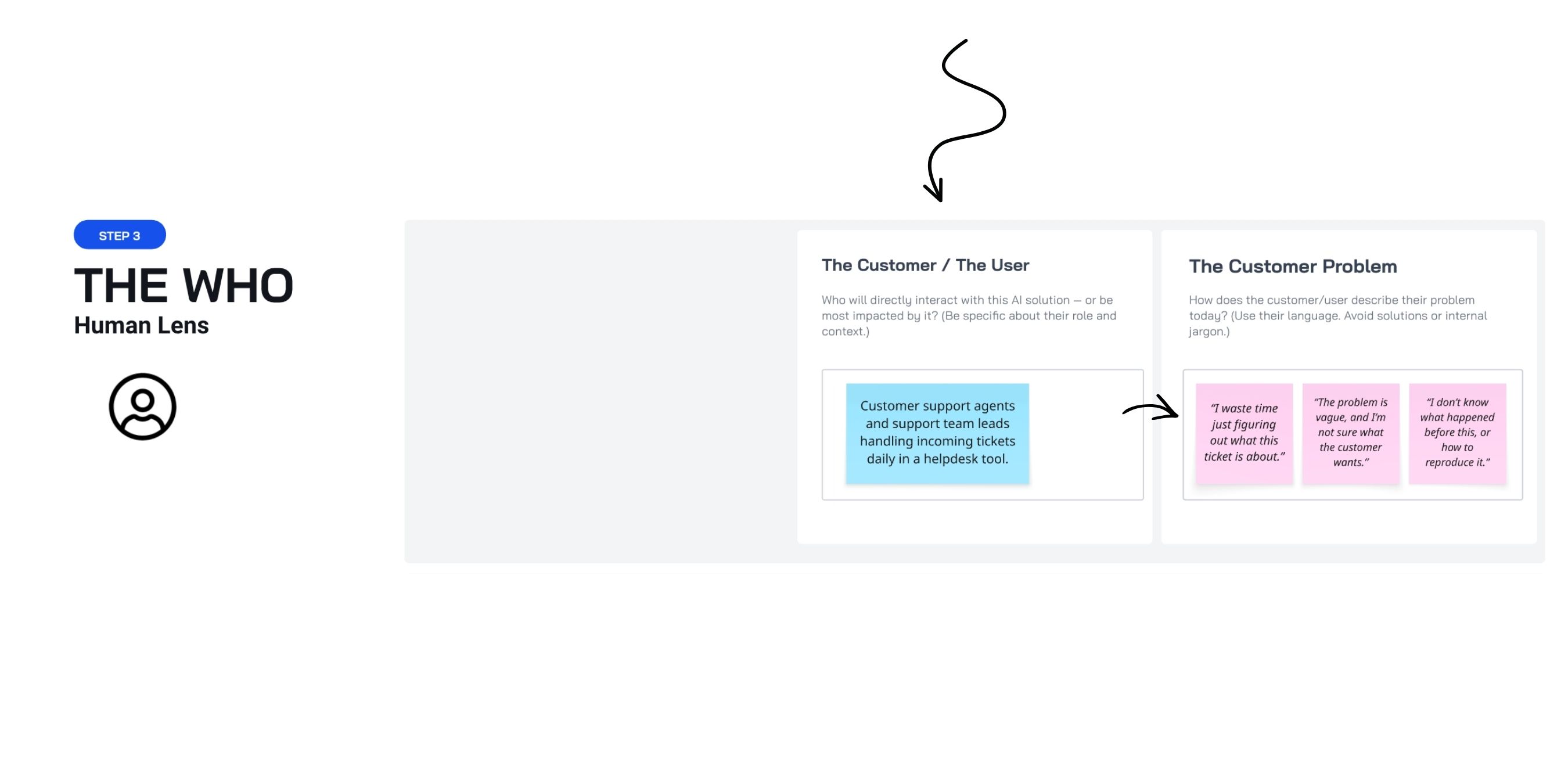

STEP 3 — THE WHO: make it real for the people using it

Once the goal is clear, shift from what you want to build to who has to use it every day.

The customer / the user

Here, you name the exact role affected.

In the support example, this might be:

“Customer support agents and support team leads handling incoming tickets daily in a helpdesk tool.”

That specificity matters because AI changes behavior—how people work, decide, escalate, and trust the system.

If you can’t name whose behavior changes, adoption is a coin flip.

The customer problem

Now you describe the problem in the user’s own words.

This is where many ideas that sound strong in planning meetings fall apart. What reads well in strategy language often doesn’t match what the work feels like.

In the support example, it might sound like:

- “I waste time just figuring out what this ticket is about.”

- “The problem is vague, and I’m not sure what the customer wants.”

- “I don’t know what happened before this, or how to reproduce it.”

Keep these lines plain. They should sound like something a person would actually say, not something an org would put in a deck.

This block isn’t where you decide. It’s where you check the story against the real day-to-day.

If the problem doesn’t show up in the user’s world, it won’t matter how well it maps to leadership priorities.

Why this step matters

This block does two things:

- It pulls the person out of internal logic and into lived experience.

- It produces a problem statement you can later test through research or observation.

Skip this and teams design workflows on paper—then act surprised when adoption stalls.

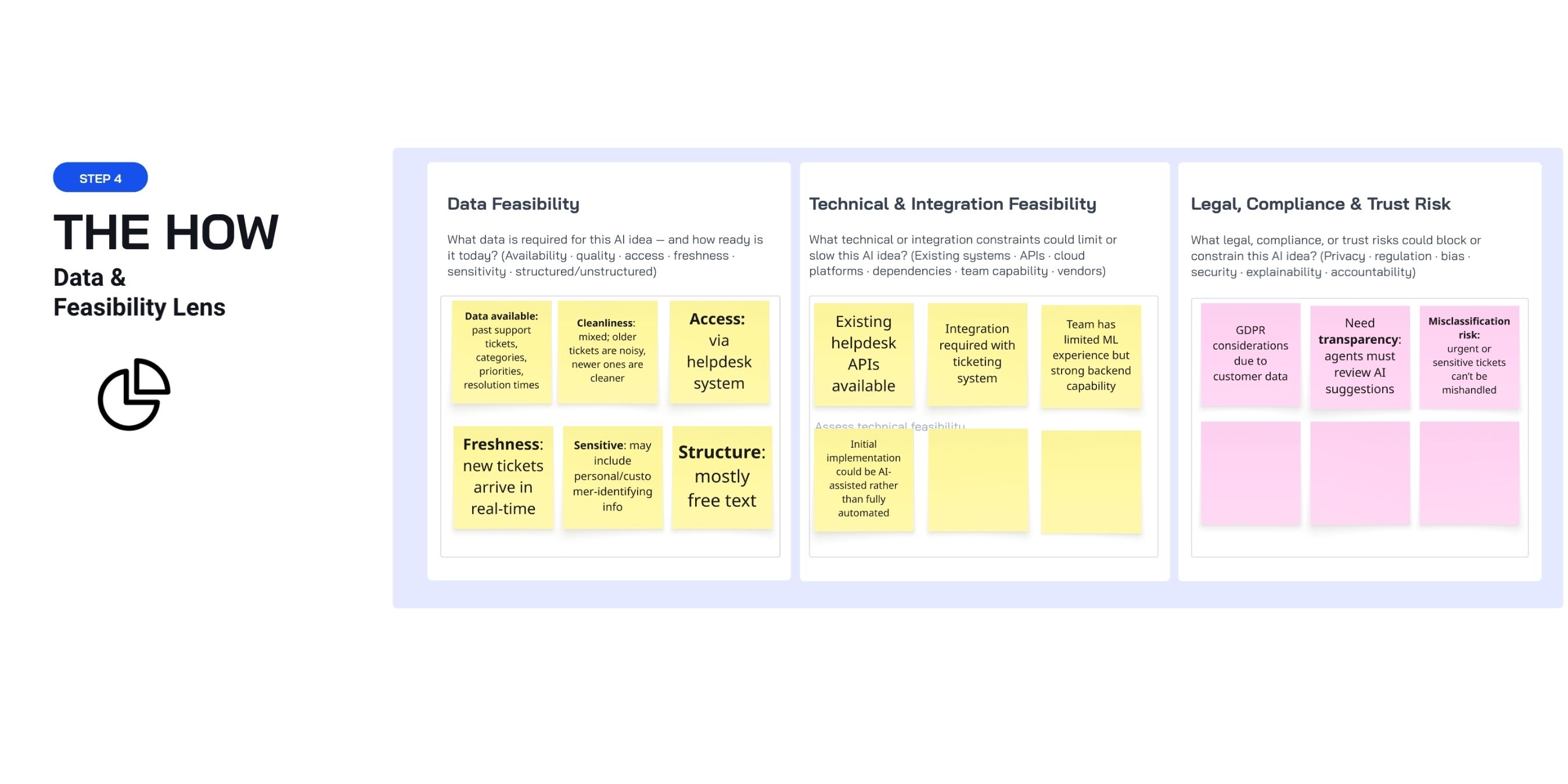

STEP 4 — THE HOW: where ideas prove they can work

This is where many ideas either stand up—or fall apart.

Data Feasibility

Here, you surface the actual data requirements behind the idea. Not in abstract terms, but based on what you have today:

- what exists

- how clean it is

- who can access it

- how current it is

- what’s sensitive

- how it’s shaped (tables, text, files)

Staying with the customer support example, this might look like:

- Data available: past support tickets, categories, priorities, resolution times

- Cleanliness: mixed; older tickets are noisy, newer ones are cleaner

- Access: through the helpdesk system

- Freshness: new tickets arrive in real-time

- Sensitive: may include personal/customer-identifying info

- Structure: mostly free text

This block does not require perfect answers. But it does require honest ones.

The goal is to make prerequisites visible before people build on guesses—and before you hit the late-stage wall: “We can’t do this with the data we actually have.”

You may not know everything at this stage. So, if you’re proposing the idea, this is where you start checking:

- talk to data engineering

- look up the systems of record

- confirm what exists, where it lives, and what rules apply

These aren’t small details. They’re constraints that don’t care how good your idea sounds.

Tech & integration reality

Now deal with the system it has to live in. This is where APIs, dependencies, platforms, and team capability come into play.

Staying with the support example, the picture might look like this:

- the helpdesk has APIs to read and update tickets

- you’ll need to connect into routing and workflow rules

- the team has limited ML background but strong backend/integration skills

- the first release can start as AI-assisted instead of full automation

A lot of AI work fails here because integration work gets priced like an afterthought.

Legal, compliance & trust risk

Finally, name the constraints teams like to postpone: privacy, regulation, review-ability, responsibility.

In the customer support example, this might surface considerations like:

- GDPR: you may process personal customer data

- Reviewability: agents need to see why the system suggested something

- Misclassification risk: urgent or sensitive tickets can’t be mishandled

At this point the question shifts from “Can we build it?” to “Can we ship it without creating new risk?”

These aren’t implementation chores. They’re decision constraints.

They shape:

- whether automation is acceptable

- how much human review you need

- who owns the outcome

If the idea can’t clear this step, change the scope, reframe the approach, or stop before backing out gets expensive.

That’s it. That’s how you fill in the canvas.

The AI Problem Framing Canvas doesn’t give you certainty.

It gives you something more valuable: the ability to be wrong early — instead of confidently wrong later.

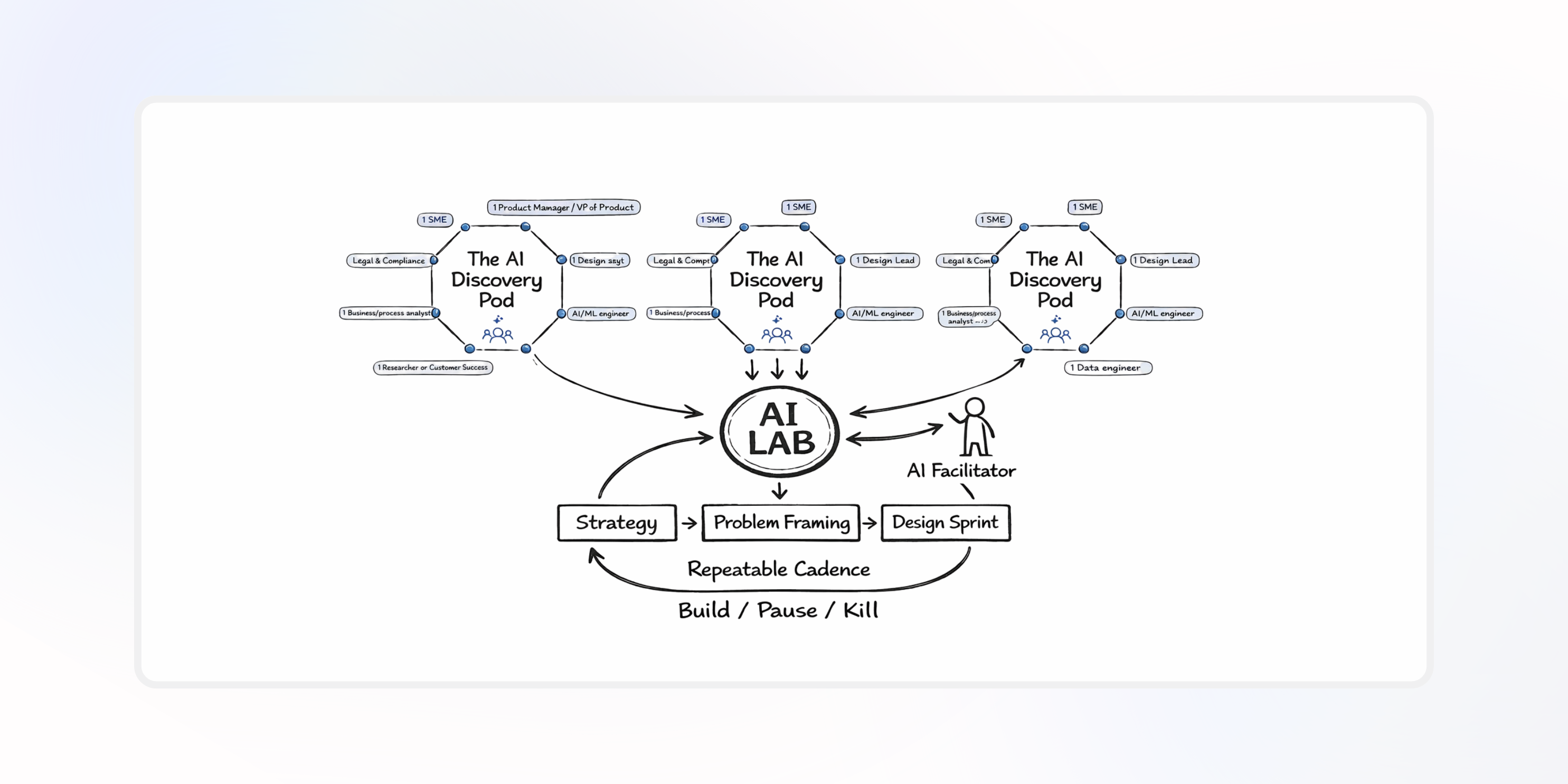

How we use the AI Problem Framing Canvas at DSA

At Design Sprint Academy, we use the canvas before and during our 1-day AI Problem Framing workshop. The goal is to decide which AI use cases are worth solving.

1) One-hour onboarding before the workshop

Before the workshop, we run a facilitated one-hour onboarding session. We meet the team, share the current context, agree on outcomes, and invite participants to bring their AI ideas.

Each person captures their ideas in the canvas on their own.

This does a few things early:

- It shows where people are describing the “same” opportunity in different ways.

- It lowers defensiveness before the group work starts.

- It makes the gap visible: nobody has the full picture yet, and stronger framing will require more input from data, systems, and the business.

2) The workshop: collecting, comparing, converging

During the workshop, we use the canvas again—this time as a tool to compare and converge.

As the team works through our framing steps, we use the canvas to:

- collect ideas in a consistent format

- compare them across the same dimensions (in our process: the magic lenses)

If you want to go deeper on problem framing, read this: AI Problem Framing 101: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How to Use It in Your Organization

For hands-on practice and more confidence, join one of our AI Facilitator Training bootcamps in 2026.

We also recorded a webinar where we detail how to fill in the AI Problem Framing Canvas.

.png)